Dead Cow Claims Trigger Controversy in Denmark

Author: Viktoria Waldvogel

In recent weeks, claims from Danish farmers alleging that their cows are falling ill due to the feed additive Bovaer have gone viral on social media. These unverified reports, which are viewed with scepticism by scientific authorities, have led to sensational portrayals and disinformation online, causing concern among both consumers and farmers. In response, Danish authorities have launched investigations into the reported cases, signaling that the concerns are being taken seriously. Similar controversies around Bovaer already emerged last year in the UK, where fears of “contaminated” milk circulated online.

Linking Cows, Bovaer, and Climate Mitigation

The additive Bovaer is designed to reduce methane emissions from cattle, a key target in climate mitigation for agriculture. Methane is a so-called “super pollutant” among the greenhouse gases and is after carbon dioxide the second largest contributor to climate change. More than 150 countries have joined the Global Methane Pledge, committing to reduce methane emissions by 30 per cent by 2030. Experts warn that fear-driven narratives and conspiratorial framing of such technologies risk undermining public trust in urgently needed climate solutions, even before the evidence is assessed.

Much of the online attention focuses on videos and quotes in which farmers allegedly describe sick animals after using Bovaer. These testimonies are often reposted with commentary or speculation, amplified by larger accounts, helping rumors spread beyond the original claims. One of the most widely shared videos shows a farmer standing inside a cowshed speaking worried to the camera. They describe that after adding Bovaer to the feed, some of their cows showed signs of sickness and low appetite, leading to a loss of “3.000 liters of milk daily.” The farmer explains that using Bovaer for at least 80 days is now mandatory in Denmark and “if you don’t do it you can go to prison or you get a really big fine.” Convinced that Bovaer is responsible for the sick animals, they conclude: “it’s just poison for our cows,” and state they have since stopped using it.

🚨 “The Law in Denmark is that we feed Bovaer to our Cows”

— Concerned Citizen (@BGatesIsaPyscho) November 4, 2025

“On Friday we had the first Cow down, on Saturday - two more Cows down”

More Farmers are coming out & stating their Cows are dying since being forced to consume Bill Gates Bovaer Animal Feed - this stuff is getting into… pic.twitter.com/vf8HbcdPtP

What is Bovaer and is it actually safe?

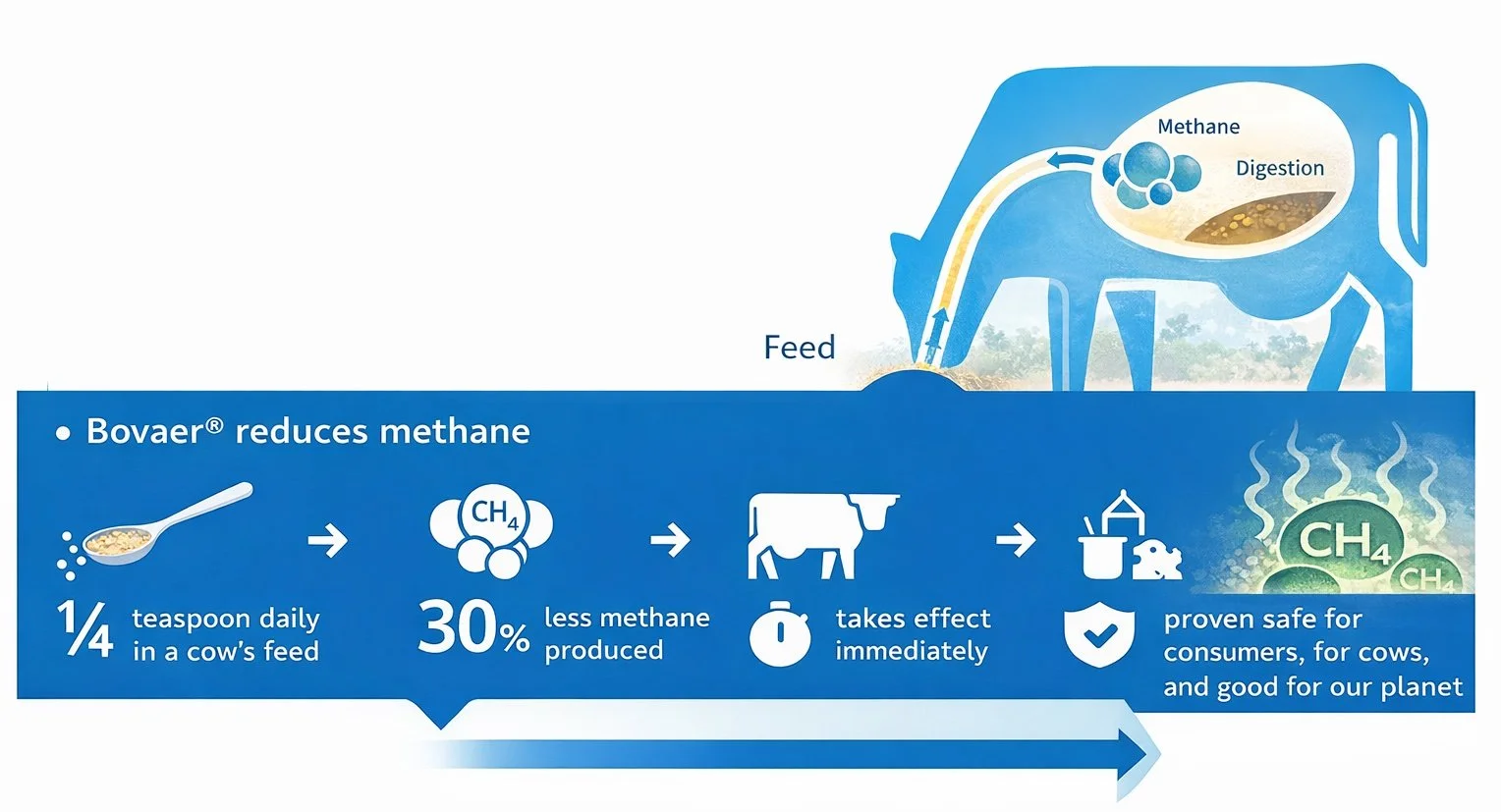

As agriculture is one of the main methane drivers, new technologies such as Bovaer are being explored as climate mitigations tools for more sustainable food production. Bovaer is an EU-approved feed additive designed to reduce methane emissions from dairy cows by up to 35 per cent.

Before Bovaer was authorised in the EU in 2022, it reportedly underwent 15 years of extensive scientific evaluation, according to its manufacturer DSM-Firmenich. The company notes this covered more than 150 on-farm trials in over 20 countries and over 100 peer-reviewed studies. The European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) concluded that Bovaer is safe for dairy cows and consumers. National food authorities, such as those in Sweden and Denmark, and the UK Food Standards Agency, similarly found no safety concerns in their assessments. As researchers at UC DAVIS note: “No other methane lowering feed additive had ever undergone more of a scientific scrutiny regarding its efficacy and safety.”

Figure: Visual showing how Bovaer reduces methane emission.

Research institutions continue to examine broader aspects of cow health and performance. A longitudinal study published in 2024 found that cows fed Bovaer produced 6.5 per cent more milk and showed improvements in milk fat and protein content as well as stable feed intake, contradicting claims circulating on social media that the additive harms milk production and appetite. Studies at Aarhus University in Denmark, which advises national authorities, have observed reduced feed intake in some cases. However, a lower appetite does not necessarily indicate that the animal is unwell. To investigate this more thoroughly, a multi-year research project was launched this year that is the first to investigate whether the additive has any welfare impacts, including whether cows avoid feed that contains Bovaer. Overall, it is emphasised that outcomes can vary with dosage, farm conditions and management practices, and that ongoing monitoring of animal responses remains important. By now, Bovaer is approved for use in 70 countries, including Australia, Brazil, Canada, and Japan.

Why the controversy is not new

The controversy surrounding Bovaer is not new. Unfounded rumors and misinformation about “contaminated” milk connected to Bovaer were already circulating in the UK a year ago. Internet users called for a boycott of large corporations such as Arla, a major dairy company, with its products being demonstratively poured down the drain. Some connect the additive to a “Bill Gates vaccine” conspiracy and alleging a government cover-up. While Gates has no connection to Bovaer or DSM-Firmenich, he has invested in a rival startup which develops a similar product using seaweed. In December 2024, both AFP and Reuters published fact checks addressing these claims, concluding that there was no evidence that Bovaer posed health risks to either animals or humans.

“Cowspiracy” 2.0 hits Denmark now

In the last weeks, accounts such as Kent Nielsen, Peter Sweden and the Food Files, among self-proclaimed “people journalists” have been sharing stories and videos of allegedly sick cows in Denmark, claiming Bovaer to be unsafe. Posts describe symptoms including reduced appetite, diarrhoea, and lower milk yields, alongside more dramatic allegations of collapsed or dead animals said to be linked to the additive. As these narratives spread, comments reveal anxious consumers regarding the safety of dairy products and concerns that Bovaer may not have been sufficiently tested before being introduced on farms.

Cows in Denmark are collapsing and dying due to Bovaer poisoning. The authorities are not doing anything to stop it, but are allowing it to continue.

— Kent Nielsen Denmark (@Kentfrihedniels) November 4, 2025

Credit for the video @lillehj https://t.co/pOlos8Dt9K see more about Bovaer on https://t.co/9YKJaUXWRL

Kent Nielsen 11/4 25 pic.twitter.com/xBDriQha3i

The Consequences

Even though it first appeared that the noise only came from the climate deniers’ corner, the allegations have now reached local and international news and led to the Danish authorities investigating these cases. On November 12, 2025, the Danish newspaper Politiken reported that around 150 farmers had encountered such significant difficulties in connection with Bovaer that they had paused its use. The Danish green party “Alternativet” has demanded a suspension, while the government continues to defend the additive’s safety, only allowing exemptions for sick animals. Norway temporarily paused the use of Bovaer as a precautionary measure while awaiting more data, despite stating that no cases had been documented domestically. Jannik Elmegaard of the Danish Food and Veterinary Administration told the BBC that officials are “very aware” of the reports from herd owners and are closely monitoring the situation.

Regulations and Ongoing Investigations

Contrary to claims in the viral video, Bovaer is not legally mandatory in Denmark. However, it is one out of two options for conventional dairy farms with more than 50 cows which are required to reduce methane emissions under Danish climate regulation. Farmers can either use Bovaer for at least 80 days per year, or feed cows a higher-fat diet. In practice, most farmers have opted for Bovaer, as increasing fat levels across the entire year is considered physiologically challenging for cows and economically unattractive, according to Kjartan Poulsen (Danish National Association of Dairy Producers) explaining to the Danish broadcaster DR. As to the Danish Food and Agriculture Association over 1,435 farmers, representing roughly 446,650 cows, are using Bovaer in 2025, supported by subsidies covering up to 85% of costs.

In response to numerous enquiries from the cattle industry, SEGES Innovation, a Danish agricultural research and advisory body, launched a survey to collect farmers’ experiences with Bovaer. As responses mainly come from herds reporting problems, the data is not representative. SEGES cautioned that many farms introduced Bovaer alongside other feed changes, so no causal link can currently be established.

Climate Solutions Under Pressure

Images of visibly distressed farmers, accepting financial penalties over feeding what they perceive as a harmful substance to their cows, have proven emotionally powerful. However, there is currently no solid evidence for mass cattle deaths, nor for a proven causal link between Bovaer and the reported illnesses. How exactly Bovaer was applied on individual Danish farms, whether dosage guidelines were followed, or whether other factors such as seasonal feed changes played a role, remains unclear. This uncertainty does not invalidate the farmers' experiences, but it does call for caution when it comes to drawing conclusions based solely on isolated observations.

The debate highlights a tension: reducing meat and dairy consumption is unpopular, while mitigation technologies are being critically questioned. Evidence, transparency, informative science communication, and careful monitoring are key to navigate these conflicting pressures. Experts have warned that fear-driven conspiracies could hinder future climate mitigation efforts. Reuters warned that the backlash against Bovaer could discourage food companies from experimenting with urgently needed climate solutions. Transforming food systems will take time and likely involve multiple approaches, including fewer cows, plant-based alternatives, mitigation technologies, and patience for trial and error.

Bovaer is neither the first nor the last attempt to reduce methane emissions from livestock. Research into methane-reducing feed additives is diverse and ongoing. Scientists at LMU Munich are currently developing a new feed additive that could cut emissions by up to 80 per cent and be on the market within the next five years. Bovaer, in other words, is unlikely to be the final word in this field.